Erin McGee Ferrell: The Art of Cancer Advocacy

Advocate Spotlight May 2022 – Erin McGee Ferrell

Advocate Spotlight May 2022 – Erin McGee Ferrell

Erin McGee Ferrell’s cancer was discovered during a traditional ceremony in a small Ecuadorian town along the Amazon River. She’d been traveling as an independent artist for five weeks, researching natural paints and pigments from Amazonian plants and minerals. Although she felt fine throughout her travels, a medicine woman used an egg to determine that “something was off.” Three months later, Erin felt a lump in her breast.

As a survivor of two bouts of melanoma and a carrier of the BRCA2 gene mutation, Erin was familiar with how vigilant she needed to be throughout the journey ahead. Still, the emotional strain associated with undergoing a double mastectomy, chemotherapy, radiation, and oophorectomy were especially challenging. Erin, a visual artist and art professor at The University of New England, processed what she endured by creating paper dolls that reflected each stage in her recovery. After receiving positive feedback from survivors and members of the medical community, Erin launched Pirate Crew Paper Dolls and sold them as a cancer educational tool.

Today, three years after her breast cancer diagnosis, Erin embraces life’s opportunities. She recently visited Bahrain, where her husband is deployed for 11 months, to spend a month creating art with sailors and their families. While speaking with personnel on the military base, Erin learned that active-duty service members are often asked to leave duty for treatment. She didn’t hear or see information about cancer screenings or cancer awareness while there, despite learning from a Bahraini breast surgeon that the rate of breast cancer diagnoses among people in their 20s is on the rise. Erin’s interactions on the military base sparked her interest in understanding how active-duty servicemembers — particularly women who are recently diagnosed with breast cancer — navigate learning about their diagnosis and receiving treatment in this environment.

Erin’s quest to understand the experiences of breast cancer survivors in the military is personal. She’s the mother of a man in the Army who is hesitant to get tested for the BRCA2 gene mutation. “I think that whole mindset of the military, especially for guys, means that they just have to be really big and tough,” she says. Erin understands that the possibility of a breast cancer diagnosis would be difficult for her son to cope with, as it may challenge traditional ideas of masculinity among service members. She hopes more men will advocate for cancer awareness in the military.

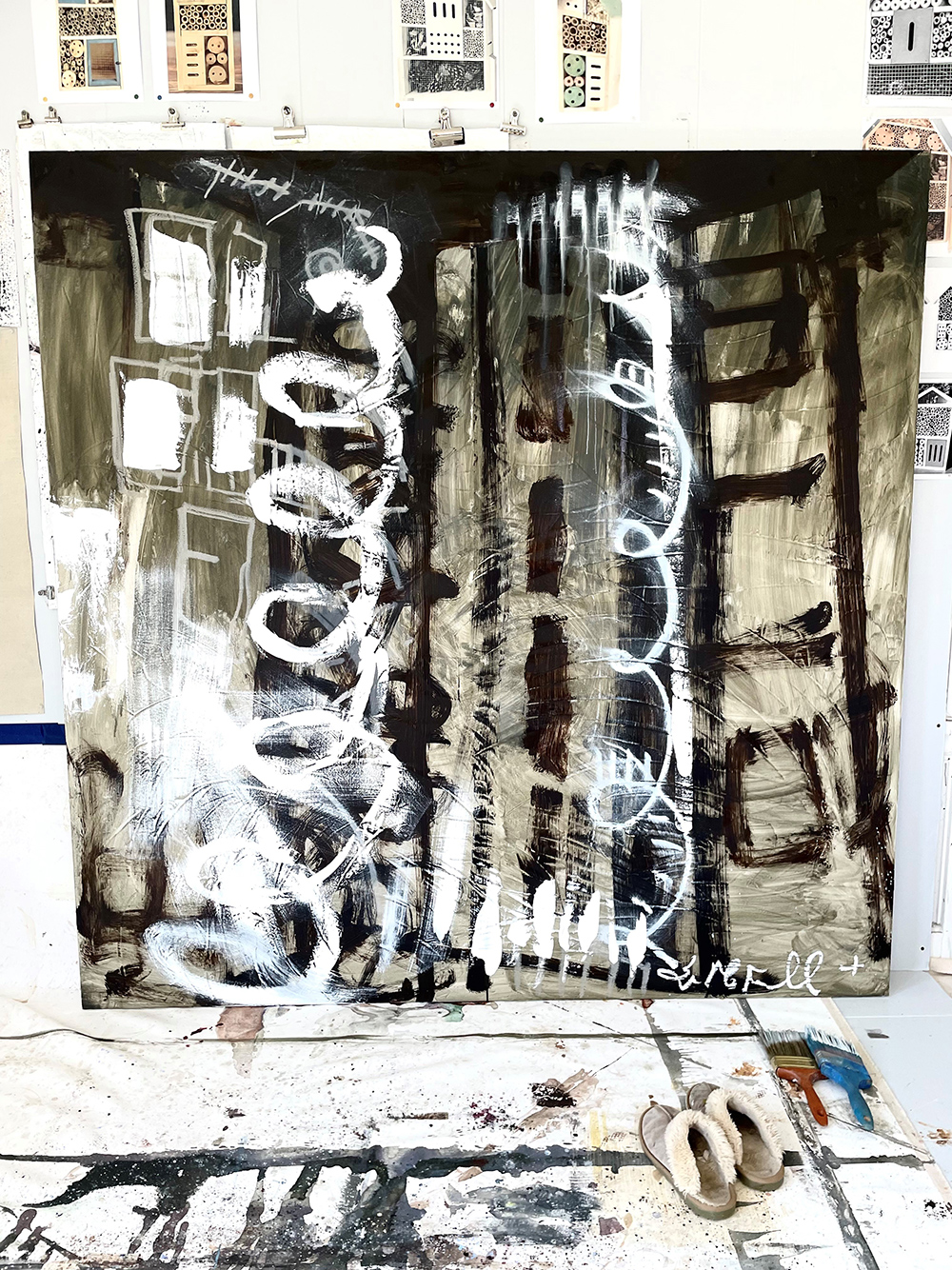

Erin’s slippers beside her finished oil painting, “Athens.” This 72 x 72-inch oil painting depicts two 14-story spiral staircase fire escapes that she saw in Greece. She connects this architectural scene with the larger meanings of risk, fear, facing danger, and seeing beauty in the unexpected.

Although Erin values information, she understands how it feels to be overcome by what she describes as a “bad news concussion.” She was no stranger to the world of cancer at the time of her breast cancer diagnosis, yet she recalls feeling the sensation of a cotton-filled football helmet coming over her head and decreasing her range of thinking from three-feet long to three-inches long. Within 60 seconds, Erin lost the ability to process what her doctor was telling her, and she was overwhelmed by thoughts of sharing the news with her friends and family, canceling and rescheduling future work plans, choosing an oncologist, deciding whether to get her cancerous nipple removed, and purchasing items to support her during the recovery. This experience drives her interest in advocating for improved methods that physicians can use to communicate bad news and for recently diagnosed survivors to receive it.

Through her work as an artist and professor, Erin bridges the gap between art and patient advocacy. Over the years, she’s been involved in local, national, and international opportunities to conduct research, educate others, and navigate the world of art and science. She’s currently participating in a traveling art and cancer exhibition to help reduce the stigma of diagnoses in other countries by fostering conversations about cancer.

Erin’s studies of world cultures have opened her eyes to the need for patient advocacy in countries where there is no such thing, like Greece and countries in the Middle East. In discussions with international breast cancer surgeons and survivors, she realized how much of a privilege it is for American patient advocates to talk about cancer openly and to raise issues with the government. “The fact that we even have a voice, have a respected opinion, and that cancer is so much less of a stigma in our country than it is throughout the world is something that I took for granted until my experience traveling the last three months,” she says.

Erin’s three cancer diagnoses have not only reminded her of the uncertainty of what the next day may bring, but they have also reinforced her belief in the importance of jumping into new opportunities and living life to the fullest. “I am a woman of faith, and I feel like I have had many close calls with death over my life,” she says. “The fact that I’m alive now is pure gift.”

Art gallery: www.artistamerican.com

Instagram: @artistamerican

Twitter: @ErinMcGeeFerrel

Facebook: Erin McGee Ferrell

LinkedIn: Erin McGee Ferrell

# # #