Reflections on Cancer Survivors Day: Managing Survivorship for a Lifetime

Post by Ellen Stovall, NCCS Senior Health Policy Advisor and 42-Year Survivor

On Sunday, June 7th, we are reminded by cancer centers to celebrate National Cancer Survivors Day®. Today, there are a sea of colors for different cancer ribbons and wristbands, e.g., the ubiquitous pink for breast cancer, amber for bladder cancer, grey for brain cancer, yellow for all cancers, and so on. But many of us do not wear our colors on our sleeves or our survivorship on our wrists.

For many, Survivors Day may be a day to be reminded of a life forever changed by a cancer diagnosis. For others, it becomes a date to mourn the loss of someone we lost too soon to cancer. But for the majority of the thousands of survivors I have met over the past 40 years, our survivorship cannot be wrapped around one day on the calendar.

As one of more than 14 million people in our country who can use the word “survivor” to classify myself, (having had three diagnoses of cancer over the last 42+ years), and having been the leader of a national organization—the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship (NCCS)—that coined the term “survivorship” in 1986, I can say that no greeting card or Survivor’s Day observance adequately quantifies what this experience is like. Survivorship—the period between a diagnosis and the rest of one’s life—does change one’s outlook. As time passes, the emphasis for most of us “long-termers” shifts from length of life to quality of life. This puts a different spin on those who cling to the length of one’s years as a measure of successful treatment, rather than how those years are lived—often with disfigurement, chronic pain, and the specter of other diseases caused by one’s initial treatment regimen, including premature aging. And then there are for some second and third cancer diagnoses.

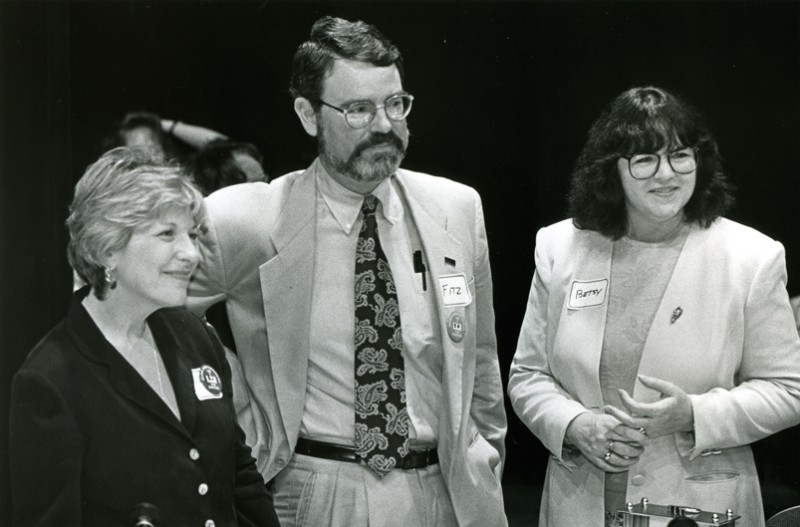

Ellen Stovall, Dr. Fitzhugh Mullan (NCCS founding member), and Dr. Elizabeth J. Clark

As a 24 year-old wife and mother to our four-week old son, Jonathan (he is now 43), I was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s Lymphoma in 1971. Following surgery and six months of radiation, a recurrence of the same diagnosis appeared 12 years later followed by a diagnosis of bilateral breast cancer seven years ago, resulting in a double mastectomy. Those are my cancer diagnoses. There is no wristband or day to commemorate the consequences of the treatment. I, and millions of others like me, live with a number of reminders of our survivorship. Daily living with a heart, lungs, kidneys, bones and tissues that look and feel like those of someone 20 years older than my chronological years is both a clinical and psychological adjustment that most of us survivors experience, but is little discussed.

What most people diagnosed with cancer want is to be cured of the cancer itself; what few oncologists and their patients understand or even want to discuss are the consequences of those treatments and how they should be managed. This is the world of cancer survivorship, and that population of survivors grows exponentially every day in large part because of the improvement in bringing new therapies forward to treat our cancer. Knowing there are short and long-term consequences of those treatments is part of the planning for survivorship that must begin at diagnosis. Choosing treatments with fewer long-term effects or intervening to prevent some of those effects is also needed.

Let me be clear about how grateful I am for my survivorship. And my gratitude is compounded by my good fortune of having a supportive family, good health insurance, and a keen interest and study of health policies that can improve the quality of care we receive. But balloons, cards, and one day devoted to cancer survivors does not begin to scratch the surface of the suffering that cancer survivors endure, including not being able to afford the care that may arrest our disease or the side effects that contribute to our enduring a poorer quality of life as we age. We survivors are supposed to be grateful to be alive and simply learn to live within a health care system that doesn’t know what to do with us. For my millions of fellow survivors, and especially for our most vulnerable to these consequences—our children and young adults with cancer—who live in this Humpty Dumpty nether land, I wish you more than one day—I wish you all many days, years, and decades of survivorship.

Please know that what has happened to us matters. One day, following completion of our initial treatment for cancer, we will have visits with our doctors and nurses that create and implement (with us) a survivorship care plan that gives us a roadmap that we presently don’t have. This plan will allow us to receive the appropriate follow-up surveillance and care to afford us a better chance for a better survivorship, with fewer hazard signs and potholes to navigate in the future.

Almost thirty years after defining survivorship, NCCS remains dedicated to changing the healthcare system to ensure that every cancer survivor receives a plan and appropriate survivorship care. As we at NCCS advocate for health policy changes, along with our research community allies, we are raising our voices for positive change.