Cancer Survivorship: You’re Never Really Done

Post By Ellen Stovall, Senior Health Policy Advisor and 42-Year Survivor

When the Imperatives of Quality Cancer Care were written by NCCS 20 years ago, one principle of quality care stated that, “Long-term survivors should have access to specialized follow-up clinics that focus on health promotion, disease prevention, rehabilitation, and identification of physiologic and psychological problems. Communication with the primary care physician must be maintained.”

It was NCCS’s vision two decades ago that there would be enough evidence to support access to and insurance coverage for interventions for short and long-term survivors related to promoting health, preventing disease, and both physical and psychosocial rehabilitation. In 2015, we are happily closer to realizing some parts of that vision, but far from able to implement it across all populations and inclusive of all settings where post-treatment cancer care is offered.

Like most of us treated for cancer, being finished with treatment is simply another stage of what we call survivorship—the act of living with, through, and beyond the diagnosis. In fact, cancer survivorship from diagnosis through the end of life has its own roadmaps fraught with much uncertainty. Each of the more than 14 million cancer survivors among us has their own story of survivorship.

As a 24 year-old wife and mother to our four-week old son, Jonathan (he is now 43), I was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s Lymphoma in 1971. Following surgery and six months of radiation, a recurrence of the same diagnosis appeared 12 years later followed by a diagnosis of bilateral breast cancer seven years ago, resulting in a double mastectomy. Those are my cancer diagnoses. And then there comes daily living with a heart, lungs, kidneys, bones and tissues that look and feel like those of someone 20 years older than my chronological years. These clinical and psychological adjustments that most of us survivors experience are little discussed.

What most people diagnosed with cancer want is to be cured; what few oncologists and their patients understand or even want to discuss are the consequences of those treatments and how they should be managed. This is the world of cancer survivorship, and that population of survivors grows exponentially every day. Knowing there are short and long-term consequences of those treatments is part of the planning for survivorship that must begin at diagnosis. Choosing treatments with fewer long-term effects or intervening to prevent some of those effects is also needed.

I am a privileged cancer survivor. I have access to a specialized follow-up clinic, but have been less successful in having my many specialists communicate with one another to determine the best surveillance and course of ongoing interventions that may be needed. Consequently, I remain one of many survivors who are captive to a healthcare system where duplicate tests are ordered and there is little, if any, coordination of care among my physicians. And so I created my own plan for follow-up care, which at the time of my diagnosis was limited to clinical guidelines that said I should have CT scans and bloodwork every 3 months; then 6 months; and then yearly “for the rest of my life.” Just what I needed—more radiation exposure—but in fact, these procedures were defined as “appropriate follow-up care.”

As it turns out, my first recurrence with Hodgkin’s Lymphoma was diagnosed after I had symptoms that I instinctively knew were reminiscent of how I felt when I was first diagnosed. I had a hard time convincing my oncologist that I was ill, and only after persistent nagging for him to do more tests was the recurrence discovered. This is not an uncommon story among my fellow survivors. It was at this time on my own path of post-treatment care that I began an earnest investigation into long-term survivorship care. There was not a lot to read about, with only a handful of researchers even interested in the topic.

I began to cobble together all of my medical records and to write my own care plan. I summarized everything that had happened to me in the 12 years since my original diagnosis onto one page and, along with a list of every medicine, etc., took this information to any new doctor who saw me. I requested that a new doctor “consult” with my oncologist before prescribing any new treatments. I expect I may have been described as a “challenging” or “difficult” patient, despite how polite I considered myself to be.

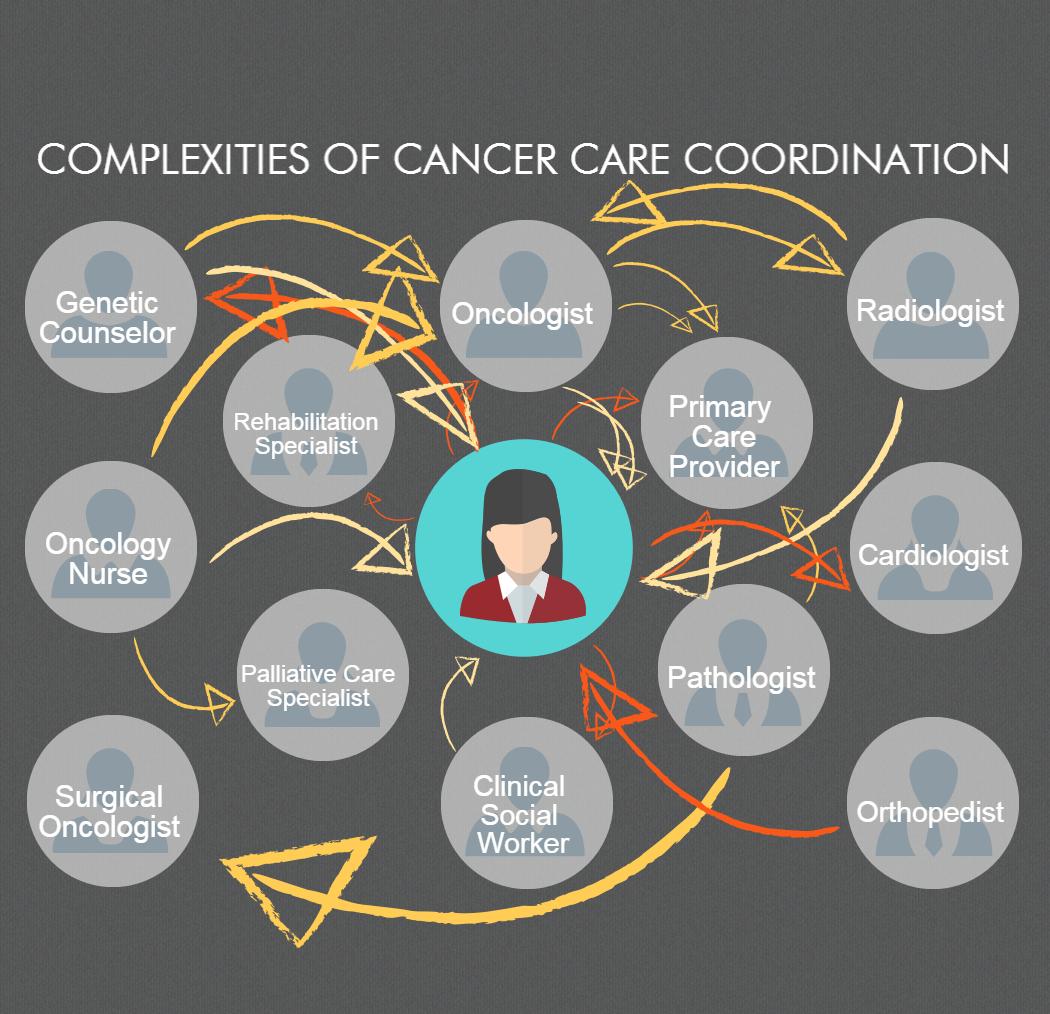

Over the years, advocacy on the part of many organizations has made follow-up care for cancer survivors, less of a “one-off” notion. The exercise of shared decision-making and care planning is being brought into discussions regarding new delivery and payment models for cancer care among physicians and third-party payers of healthcare. What follows is a graphic illustration of the care planning process. While we may not realize the full vision of follow-up clinics to deliver this care, we are beginning to see a systematic incorporation of some essential elements of best practices in the processes for making important decisions about our treatment options when we are first diagnosed. This will go a long way towards mitigating some of the late effects of cancer treatment.

This diagram illustrates the complexity of cancer care coordination. With clinical, procedural, and other supportive office visits, cancer patients may need to coordinate care with additional members of their care team, including a nurse navigator, a psychotherapist, occupational therapist, neurologist, hematologist, gynecologist, urologist, pulmonologist, or other providers. This diagram is adapted from “Ambulatory Care Coordination for One Patient” from Instant Replay — A Quarterback’s View of Care Coordination, a perspective piece by Matthew J. Press, M.D.