The Birth of the Cancer Survivorship Movement and How It Transformed Cancer Care for Millions

Guest Post by Judith L. Pearson

Best-Selling Author of From Shadows to Life: A Biography of the Cancer Survivorship Movement

“Survivorship has been my passion for three decades, so I might talk your ear off!” When Susie Leigh sent those words in an email to me in the summer of 2017, I had no idea what a journey she and I would take together.

I’m a nonfiction writer by profession, a biographer to be precise, with a voracious penchant for history. After my diagnosis of triple negative breast cancer in 2011, I just couldn’t find the next great story to tell. But I did come across some pre-cancer research about the health benefits of volunteering. Based on the theory that helping is healing, I created a little nonprofit called A 2nd Act, www.a2ndact.org. And through it, I was introduced to Susie. When we met for lunch, she made good on her promise of talking. Not only did my ears not fall off, her amazing story left me yearning for more.

Susan Leigh, RN

To best understand how momentous those births were, it’s important to understand survivors’ lives in the first three-quarters of the 20th century. Human beings had learned that deadly diseases were contagious. Based on that premise, it was presumed cancer was contagious as well. Those with a history of the disease kept quiet about it. They could lose their jobs and their health insurance (if they had that luxury), they couldn’t join the military, and they couldn’t adopt children. If invited to others’ homes for a meal, they were served with disposable plates, cups and silverware so their “germs” wouldn’t be spread. They lived as social pariahs, if they lived at all.

It is as if we have invented sophisticated techniques to save people from drowning, but once they have been pulled from the water, we leave them on the dock to cough and splutter on their own in the belief that we have done all that we can.

— NCCS Founding President Fitzhugh Mullan, MD

From “Seasons of Survival” [PDF]

Survivorship numbers hovered between 30 and 45% until the 1970s, when a marriage between politics and research took place. The prospect of President Richard Nixon having a second term was looking iffy. The nation was embroiled in an unwinnable war in Vietnam, for which Nixon had claimed knowledge of a secret, albeit never appearing, solution. Racial and anti-war protests topped the headlines, along with the president’s declining popularity. And then aides brought Nixon news of a bill making its way through Congress. Among other items (most of which were tossed out before they were done), the bill would infuse $1.3 billion into cancer research (the equivalent of $8.4 billion today).

The founding members of NCCS at the founding meeting in Albuquerque, NM, October 1986.

Cancer was a bi-partisan disease. Democrats feared it as much as Republicans. Such a bill would certainly improve Nixon’s popularity and deliver him a second term. So on December 23, 1971, he signed the National Cancer Act and won reelection the following year. Some in the administration even claimed that research from the “war on cancer” would produce a cure by the nation’s bicentennial. That, of course didn’t happen, but another miracle did: treatments improved and people actually began surviving. They still, however, lived in the shadows.

Referred to as “victims,” the unconscionable cancer myths persisted. Equally frustrating was the fact that there was no research about and little support for the people who finished the acute phase of their treatment. Dr. Fitzhugh Mullan, one of the Albuquerque weekend organizers and a very vocal proponent of their work, described the scenario eloquently: “It is as if we have invented sophisticated techniques to save people from drowning, but once they have been pulled from the water, we leave them on the dock to cough and splutter on their own in the belief that we have done all that we can.”

Two of the weekend’s primary goals were to give post-treatment patients a name and to define survivorship. The group did both in one sentence: “From the time of its discovery and for the balance of life, an individual diagnosed with cancer is a survivor.” Diagnosis is the moment we begin surviving cancer, not the moving goal line of three or five or ten years, depending on type and stage.

By the time the 23 left Albuquerque after that weekend, they had also named their organization, written a charter, and taken up a collection to get the ball rolling. These were pre-technology years. Fax machines were just being marketed and long distance was expensive. Everything was communicated via the U.S. Postal Service. Catherine Logan – the weekend’s other organizer – was named the first NCCS executive director, and dedicated space within her own nonprofit’s office for NCCS use.

Hundreds of thousands gathered on the National Mall on Sept. 26, 1998 for THE MARCH, organized by NCCS. More than a million people total across America participated in local events.

Because of the dedication of that first group, and all who have come after in the movement, survivorship came out of the shadows. There have been many crowning moments in NCCS history, perhaps most momentous of which were the creation of the Office of Cancer Survivorship at the National Cancer Institute, and the 1998 March on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., which drew more than 200,000 participants.

As NCCS grew, a previously seldom-used term was also brought to light: advocacy. It is the umbrella under which all the movement’s work resides. Ellen Stovall (who was the NCCS CEO from 1992-2008, and continued as Senior Health Policy Advisor until the time of her death in 2016) and Dr. Elizabeth “Betsy” Clark (who was an oncology social work pioneer and held various roles at NCCS including board president) co-authored a wonderful article about its different types, from self-advocacy, to advocating for others, to advocating before governmental bodies. And advocacy is not only good for the recipients. It’s good for those doing the work, as well. Remember, helping is healing.

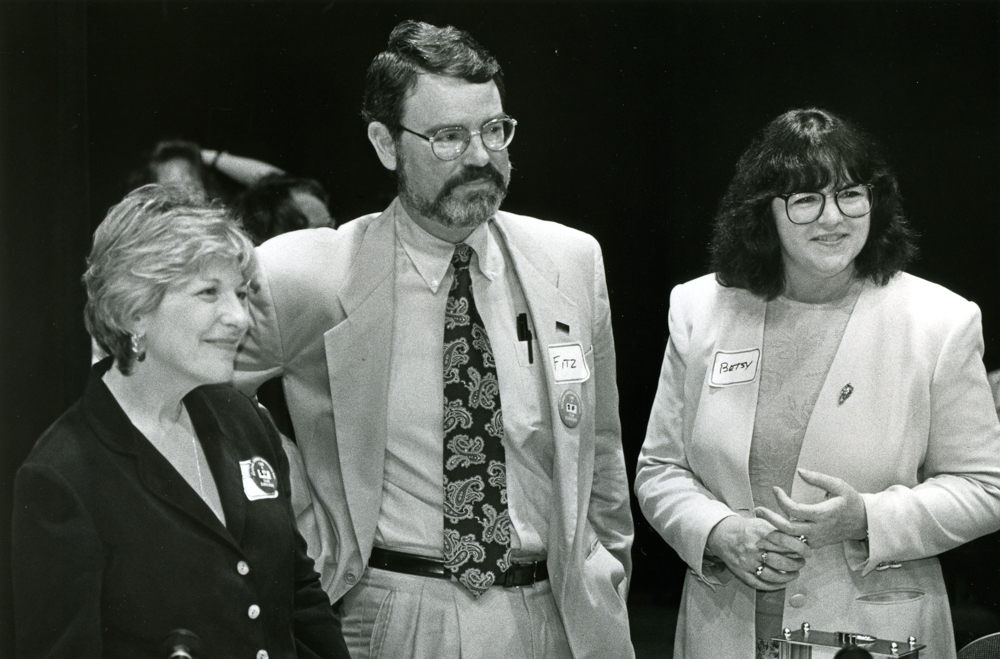

Ellen Stovall, Fitzhugh Mullan, MD, and Elizabth “Betsy” Clark, PhD

As I mentioned earlier, biography is my gig. And history lights me up. It became clear to me from the very first meeting with Susie that this was the next great story I was meant to tell. From Shadows to Life: A Biography of the Cancer Survivorship Movement (published March 2, 2021) follows the stories of those who launched and led a movement that has changed the lives of tens of millions around the world.

I’m often asked what work still needs to be done in survivorship. My answer is simple: we – survivors, co-survivors, health care workers – must make certain the movement lives on. We must continue to advocate for survivorship research and survivorship health care coverage. We must insist that survivorship be considered a part of the cancer continuum just as diagnosis and treatment are. We must do this in honor and in memory of those who had the courage to begin it 35 years ago.

The cover of my new book features a phoenix. According to ancient legend, the phoenix is a bird that burns to death and is reborn from its own ashes. As the symbol of renewal and rebirth, it is a perfect metaphor for cancer survivorship.

Susie recently said, “I am again wondering why I am so lucky to still be here. I guess I still have work to do.” She’s spot on. We have been given extra days on this earth. Let’s make them count!

About Judith L. Pearson

Judith L. Pearson

Judith L. Pearson’s previous books include Wolves at the Door: The True Story of America’s Greatest Female Spy and Belly of the Beast: A POW’s Inspiring True Story of Faith, Courage, and Survival Aboard the Infamous WWII Japanese Hell Ship Oryoku Maru.

A diagnosis of triple negative breast cancer led Judy to found A 2nd Act, a nonprofit that raises funds through live storytelling performances, publishes a book (an ever growing collection of the stories told on their stages), conducts workshops helping guide women survivors as they discover their 2nd Acts, and makes micro grants to survivors ready to launch or grow their 2nd Acts after cancer. In 2014, she was honored in Washington, D.C., by the American Association of Cancer Research (AACR).

Judith Pearson’s Website »