WCOE: Elevating the Discussion on Living Well Until the End of Life

| What Caught Our Eye (WCOE) Each week, we take a closer look at the cancer policy articles, studies, and stories that caught our attention. |

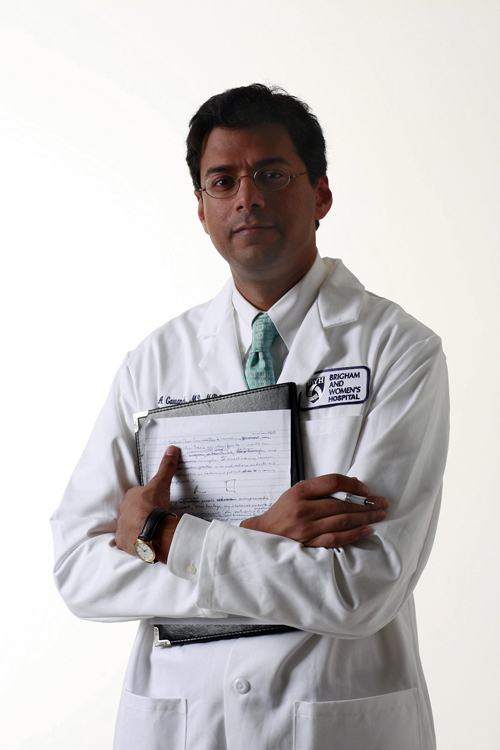

This week coverage of Dr. Atul Gawande’s new book caught our eye.

What caught our eye this week was extensive coverage of Dr. Atul Gawande’s new book, Being Mortal: Medicine and what Matters in the End. In it, he examines end-of-life care in our country, and he weaves in personal stories from his own family and his patients, as well as interviews of hundreds of patients, families, physicians, and caregivers. Excerpts were published in The New York Times and Slate, there were numerous other articles and reviews, and Dr. Gawande was interviewed on the Diane Rehm Show, PBS Newshour, and The Daily Show.

In the introduction to Being Mortal, he writes:

“You don’t have to spend much time with the elderly or those with terminal illness to see how often medicine fails the people it is supposed to help. The waning days of our lives are given over to treatments that addle our brains and sap our bodies for a sliver’s chance of benefit. … Our reluctance to honestly examine the experience of aging and dying has increased the harm we inflict on people and denied them the basic comforts they most need.”

I had the privilege of attending a book talk at the Aspen Institute this week, where Dr. Gawande said that the book originated from two pieces he wrote for The New Yorker: “The Way We Age Now” on the science of aging and “Letting Go” on the failures of our medical system in providing appropriate care to individuals at the end of their lives.

“Letting Go” was a very influential piece and helped people to initiate important conversations. A friend shared it with family members who were struggling to accept that their sister/daughter, only in her 20s, was dying of brain cancer. A colleague made it required reading for her family and used the article as a catalyst for family discussions on individuals’ wishes for treatment at the end of their lives. I have written before about my friend, Dr. Brent Whitworth, who died two years ago of kidney cancer. At one point, a few weeks before Brent died, he told me it was time to share “the article” with his family, and he asked me to print and bring copies to the hospital.

In “Letting Go,” Gawande wrote about his experience in treating Sara Monopoli, who despite the agreement to limit aggressive care at the end of life, he recalls, “we never could get off the train.” He said these experiences changed the way he took care of patients and the way he cared for his father.

In Being Mortal, he writes about the lessons learned from interviewing palliative care experts, oncologists, gerontologists, hospice workers, and nursing home staff. He looked for what he called “positive deviants,” or people who are doing exceptionally well, who have “perfected the craft.”

He describes two lessons: “First, in medicine and society, we have failed to recognize that people have priorities that they need us to serve besides just living longer. Second, the best way to learn those priorities is to ask about them.”

He suggests questions that physicians can ask patients, including, “(1) What is their understanding of their health or condition? (2) What are their goals if their health worsens? (3) What are their fears? and (4) What are the trade-offs they are willing to make and not willing to make?” These questions align with the questions in our Know Yourself worksheet, a tool NCCS created to help prepare patients to have these conversations with their care teams and families.

I would argue that these questions are not just for people with a terminal illness, but for anyone with a cancer diagnosis. The answers are essential to a shared decision-making process and an informed treatment choice, whether an individual with cancer has early stage or metastatic disease. Of course, our system does not provide adequate time or incentives for these kinds of conversations. Gawande points out that he is rewarded for performing surgeries, not for having difficult, sometimes time-consuming discussions with patients, even though the conversations may lead to better treatment that more closely aligns with an individual’s values and preferences.

During the book talk at the Aspen Institute, Gawande said the response to the book has exceeded expectations, and they have begun a second printing. Laughing, he said the book is even beating Bill O’Reilly’s book on Amazon’s best seller list.

My hope is that his book will help elevate the conversations between providers and patients, as well as among families, about what kind of lives we want to live and what kind of care we want to receive. As Gawande said, “The goal is not a good death, but as good a life as possible until death.”

| Post by Shelley Fuld Nasso. Connect with Shelley on Twitter @sfuldnasso. |